The Three Secrets of Great Projects

Contents |

[edit] The background and the challenge

Projects are becoming increasingly complex, with greater demands on efficiency and schedules, as well as growing competition. However, quite often, even the most ambitious and well-funded efforts suffer from extensive overruns, long delays and misrealisation of expectations, and in some cases, all of these combined.

Considering the widespread importance of projects in all industries, it appears that project management practices and techniques do not really meet the challenges of today’s projects, including many in the construction industry.

This article presents the results of a study inspired by this challenge. In contrast to other studies, which typically investigate the reasons for project failure, the authors looked at the history of large modern projects – megaprojects – dating back to the 1950s. They have been selected on the basis of multiple criteria such as efficiency, impact on the user/customer, business success and impact on society.

Among the projects studied: Apollo moon landing project, Mall of America, the Guggenheim Museum (Bilbao, Spain), the First World Trade Center (Manhattan, USA) the 2012 Olympic Village (London, UK), Los Angeles subway, and Denver International Airport.

Not all of these projects were fully successful. Study results show that the most successful projects share a combination three characteristics: clear vision, total alignment and are able to adapt to complexity.

[edit] The strategic idea and impact – Three common ingredients for success

In this study, projects were viewed as strategic processes the objective of which is to create value for different stakeholders. This approach is called Strategic Project Leadership® (SPL), whereby success is a broad concept that is measured by several criteria, not time and cost alone. The metrics are as follows:

Table 1: Strategic Multidimensional Success Metrics

| Success Metric | Efficiency |

Business/Financial Success |

Impact on Society | |

| Measurement | Time and costs | Customer/User satisfaction, improvement | Business profits, return on investment | Environment, well-being of society |

Strategic Project Leadership® views project leaders as CEOs who are responsible for achieving the expected business results, while leading their teams with high energy and motivation. In sum, project leaders must have both a short- and a long-term perspective.

They need to focus on short-term delivery requirements, as well as the economic, environmental, social and political aspects of projects. The study, searched for the common managerial and life cycle elements that enabled meeting the success criteria (metrics) described above.

[edit] Clear vision

This vision is an articulation of the end result defined in simple terms that everyone can understand and conceive. It describes the state of the environment concerned after the project is completed, often in visual or even emotional terms. Other kinds of vision also articulate what people will be able to do once the project is completed and how their lives will be affected, improved or simplified.

A vision does not deal with profits or financial performance, nor is it described in technical terms. Best visions evoke emotional reactions, such as Kennedy’s vision for the Apollo programme to “put a man on the moon and bring him back before the end of the decade.” The vision of the Mall of America was to “Build the largest and most fun mall in America.” And the first World Trade Center’s was “a commercial and trade center that will revitalize the economy in lower Manhattan.”

Good visions are created by great leaders. They are able to articulate what the project is about – customers know what to expect, sponsors can communicate better what they will create and employees are inspired to be part of it, and clearly understand how they can contribute to its creation.

[edit] Full alignment

Full alignment means that all parties identify with and commit to the goals, means and the difficulties expected in the project. Such alignment is difficult to achieve and manage. Since projects involve networks of stakeholders with different interests and agendas, the sponsor and performing life cycles must have a clear and shared understanding of the vision and how to achieve it.

Similarly, customers and users are involved upfront, and their voice is being heard and considered. After all, they will be the ones most affected by the project’s success. Finally, a successful project must be aligned with the community and environment in which it operates. Lack of alignment can cause conflicts and delays. One cannot expect to install a large creation in a public place or neighbourhood without the support of all those who may be affected.

Project teams are aware of this need and work hard to achieve such alignment. For example, the managers of the London Olympic village had a coordinated network of contractors using a set of common rules and risk sharing agreements that created a mutual interest for all.

Similarly, the builders of the first World Trade Center in Manhattan were managed by the Port Authority, which was also the sponsor of the project. Builders worked closely with New York authorities as well as with many merchant life cycles, restaurants, etc. In contrast, the Los Angeles subway was led as an engineering and technical design-and-build project. While it was created to serve millions of passengers, there was no real connect or alignment with the citizens of the city. No wonder then that when it opened, very few people used it.

[edit] Adapting to complexity

We define complexity as a factor that may inhibit the timely completion of a project. Such factors may include size, number of elements and extent of interconnectedness, but they may also include levels of uncertainty or constraints. Uncertainty may be linked to technology, financial markets, policy, economics or the environment. Constraints include restrictions, regulation or limited resources, such as time, people, or money.

Since different projects have varying degrees of complexity, clearly 'one size does not fit all'. The key to success, therefore, is to understand the degree of complexity and adapt the project’s management style to its specific level and kind of complexity. For example, in the Apollo project, NASA understood that going to the moon is extremely complex, risky and uncertain. They put in place numerous mechanisms for thorough examination and testing.

Nothing was left to chance and the mindset at the time is reflected in the statement, “it is unsafe to fly, unless there is proof that nothing can go wrong.” In contrast, although the architect of the Sydney Opera House had a clear vision from the outset, the vision was not in tune with the city or the political environment, leading to extensive conflict and unchecked spending. The project team did not anticipate the structure’s complexities and thus, builders only learned at an advanced stage of construction how to produce the orange-shaped roof slices that made its structure so unique.

[edit] Barriers, solutions and next steps

Adopting strategic mindsets and processes in project management will take time. It will also require specific methods and tools to plan, execute and review projects. Frank Gehry, the renowned American architect who built the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, implemented the full strategic approach, as he does in all of his projects.

Gehry insists on acting as the project’s CEO, and on making all the financial and modification decisions. Similarly, the Strategic Project Leadership® approach is applying the new mindset and techniques in several leading companies with great success.

Frequently, the barrier to success is tradition. Most companies still follow traditional approaches and use conventional tools of project management planning. It will not be easy to change mindsets or develop the skills and tools required by this new paradigm. This change will bring additional planning and tools to current methods. It will also educate project teams about this new approach and train young managers from day one to think strategically about their projects and their roles as leaders.

Written by:

- Aaron Shenhar, Chief Executive Officer, The SPL Group, USA, and

- Vered Holzmann, Chief Executive Officer, DeltaV Project Management, Tel Aviv University, Israel

This article was originally published on the Future of Construction Knowledge Sharing Platform and the WEF Agenda Blog.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Passivhaus social homes benefit from heat pump service

Sixteen new homes designed and built to achieve Passivhaus constructed in Dumfries & Galloway.

CABE Publishes Results of 2025 Building Control Survey

Concern over lack of understanding of how roles have changed since the introduction of the BSA 2022.

British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951

A rich heritage of decorative and figurative sculpture. Book review.

A programme to tackle the lack of diversity.

Independent Building Control review panel

Five members of the newly established, Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended, panel appointed.

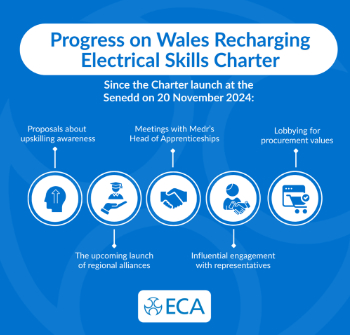

Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter progresses

ECA progressing on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.